Articles

Kargil War Defending India’s Honour

Sub Title : What has changed in the 25 years since the Kargil war? An interesting take on how the war would be fought if it were to take place now

Issues Details : Vol 18 Issue 3 Jul – Aug 2024

Author : Brig Amul Asthana (Retd)

Page No. : 17

Category : Military Affairs

: July 29, 2024

On the late afternoon of May 8, 1999, four officers and around 200 troops of the 1/11 Gorkha Rifles had just disembarked from the transport that had brought them from Leh to Kargil after a day-long journey. After a challenging tenure at Tangtse and then at the Central Siachen Glacier, the battalion was en route to Pune for a well-deserved peace posting. As the Officiating Commanding Officer, I was reflecting on our eventful tenure and looking forward to Pune, where the troops could refit, train, and reunite with their families. My thoughts were interrupted by the shrill ring of the army telephone kept in my room. The voice on the other end was sombre but clear—the message was cryptic: “1/11 GR moves no further – collect all the troops, and get them ready for action”; details would follow.

On the late afternoon of May 8, 1999, four officers and around 200 troops of the 1/11 Gorkha Rifles had just disembarked from the transport that had brought them from Leh to Kargil after a day-long journey. After a challenging tenure at Tangtse and then at the Central Siachen Glacier, the battalion was en route to Pune for a well-deserved peace posting. As the Officiating Commanding Officer, I was reflecting on our eventful tenure and looking forward to Pune, where the troops could refit, train, and reunite with their families. My thoughts were interrupted by the shrill ring of the army telephone kept in my room. The voice on the other end was sombre but clear—the message was cryptic: “1/11 GR moves no further – collect all the troops, and get them ready for action”; details would follow.

We were placed under the 70 Infantry Brigade, which itself was only a Brigade Headquarters with no troops under it, located far away in Drass but given the task in the Batalik Sector. The first elements of the Brigade Headquarters also moved to the mountainside at Dah, a small hamlet along the road, the next day.

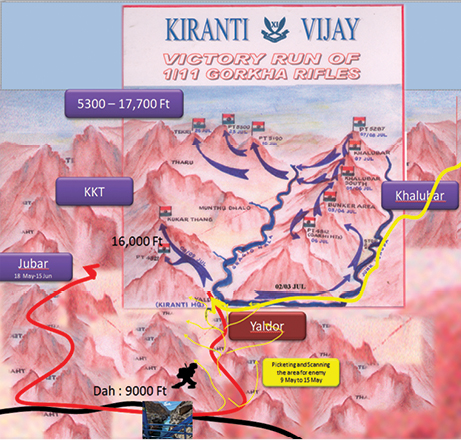

My battalion was tasked first to secure the helipad that was barely 50 meters above the road head at Dah. Some enemy fire had possibly been reported there. Thereafter, we were to secure the five ridges on the East and West along the Yaldor Nala up to Yaldor and ‘stem the ingress’ of the enemy along these heights. The next task was to recover two patrols of the holding formation that had been ambushed in the areas ‘ahead or North of Yaldor’. Their location was uncertain. Essentially, the task was to establish a large firm base to facilitate further operations to recapture our territory, which had apparently been occupied by an unknown number of enemy troops over an unknown extent. Details were limited and sketchy.

In the initial days of the operation, little was known of the enemy who seemed to spring up all around us as we climbed and captured one ridge after another, to our East and to our West, as we ascended from 9,000 feet at the road head at Dah to 16,000 feet the first day. We lacked warm clothing since it had been deposited back at Leh. We had also deposited sector maps, radios, support weapons, and first-line munitions. Medical personnel had been detached as per policy. About 60 men were out in advance parties to Pune and an enhanced leave party of 40%, besides various deployments at a number of headquarters.

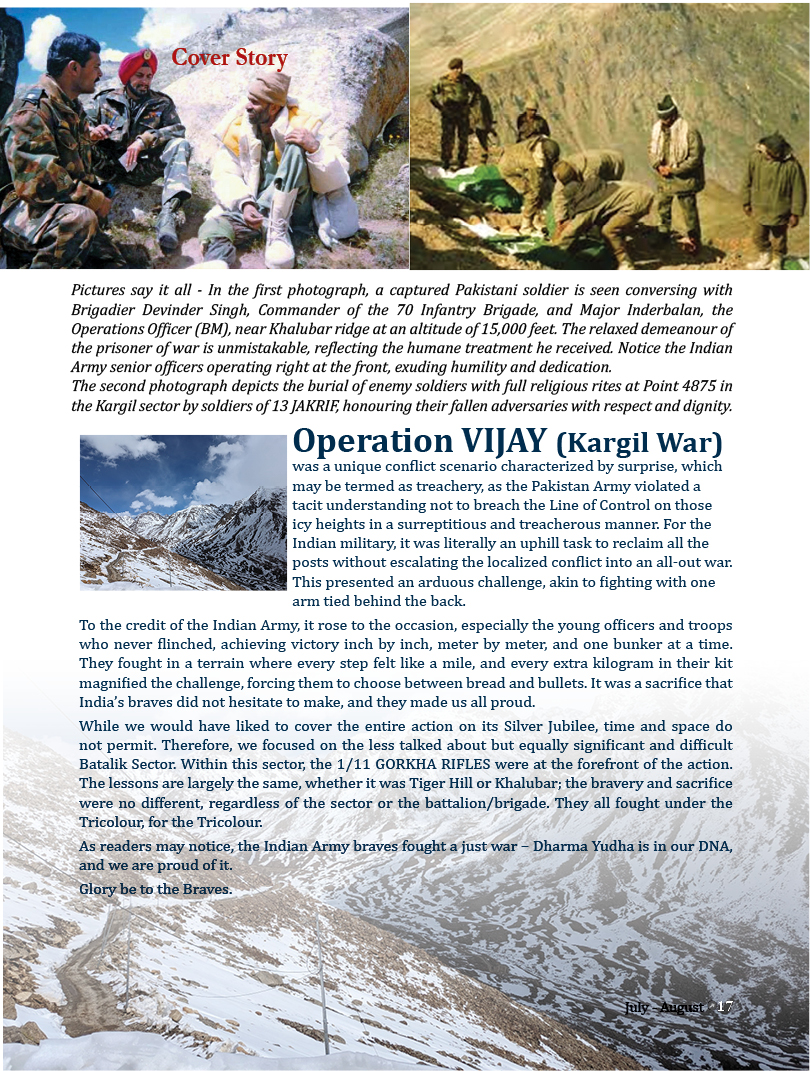

As the brave Gorkha troops, led by their officers, inched their way up, we were trying to assess what we were up against. There was fire all around us from numerous locations, even as the enemy artillery joined in and the volume of fire thickened. The accuracy of enemy fire indicated that we were being closely observed, and its ferocity suggested a coordinated effort behind such actions. Within a few hours of operations, I was now convinced that we were not just facing a handful of enemy intruders, but hundreds of them, supported by heavy weapons and artillery, and that many ridges and routes had been held by them in strength. Brigadier Devinder Singh, Commander of the 70 Infantry Brigade, who was always at the front, became aware of the ground realities and solidly backed us up. Beyond him, the hierarchy appeared convinced of a minor intrusion that they wanted to quickly overcome ‘somehow’ or ‘anyhow’.

At the front line, the biggest challenge was effectively firing on the enemy positions without support weapons or our own artillery, evacuating casualties, securing water and food, maintaining communications without maps, and navigating through snow, sleet, and rain every day. The high altitude, starting at 16,000 feet and extending up to 17,700 feet, also took a toll.

From this point, we launched a number of successful attacks, recapturing ten critical heights over an area of 15 km by 18 km and four major ridgelines, including Khalubar, Point 5287, Point 5300, and Kukarthang.

Initially, we had no support. Local porters were provided around May 29, and Commanding Officer Colonel Lalit Rai joined the battalion around June 2. Support weapons, food, ammunition, clothing, medical support, and tentage arrived over the next 15-20 days, greatly boosting our combat potential. During those 80 days, we were constantly wet (from snow, rain, and sleet), and our only set of clothes were in tatters.

The legend of the indefatigable Gorkha soldier who knows no fear was proven every moment during this experience, and my respect for the legendary Gorkhas grew even more. The myth of the much-maligned Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs) was totally busted—I never found a JCO tired, fatigued, hungry, or lagging behind; they were always leading, taking extremely bold actions. One of them even decided to continue in the war until August, despite his scheduled to retirement in June 1999.

Attack on Khalubar

The attack on Khalubar and its capture exemplifies exemplary military leadership of the highest order in the extreme fog of war. Khalubar involved numerous close, hand-to-hand combat situations across a razor-sharp ridgeline with many pinnacles extending over a kilometre at the top.

A part of Khalubar was named “Bunker Area” due to its series of bunkers along the narrow ridge line and steep sides. Capturing Bunker Area was imperative to proceed to Khalubar ridge. Captain Manoj Kumar Pandey, PVC (Posthumous), displayed exemplary courage, resilience, and craftiness, literally winning the war for us by capturing Area Bunker. He made the supreme sacrifice during this operation. By the end of June 1999, he had conducted many stupendous operations and had already been recommended for a gallantry award.

Our young officers like Lieutenant Samiran Roy (ASC att.), Lieutenant Sateesh Kumar SA (Ex AEC), Lieutenant RS Rawat (with only 28 days of service), Lieutenant KR Chandran, Lieutenant VA Joshi, and many others equally proved their courage and worth. Experienced and hardy company commanders like Major Ajai Tomar, Major JJS Rautela, Major LC Katoch, Major RP Singh, and Major C Correya also led from the front, delivering victory at every step.

Point 5287

Our assigned task was to capture Khalubar ridge, which we achieved successfully. However, we had also witnessed the MiG-21 aircraft flown by Squadron Leader Ajay Ahuja being downed on May 26, 1999. The Stinger missile was fired from Point 5287. We were now driven by a burning desire to capture the post and punish those responsible. My Company JCO (B Company), Subedar IP Limbu, said in Gorkhali, “Saheb, tyo post capture garnu parchha” (Sir, we must capture that post). We devised a plan to capture the formidable Point 5287, which was flanked by steep cliffs and had a very narrow, rugged approach, presenting a massive challenge. With a clever strategy, a solid fire support plan, and a handful of troops (about 35), we captured Point 5287 on July 8. Here, we recovered the fired Stinger missile casings that had downed the MiG-21 and another live Stinger missile. We killed the officer who had fired the missile in close-quarter combat. His diary, written in English, revealed all the details. We also captured a 12.7mm Air-Defence Machine Gun (ADMG) that had been targeting us all the way to Yaldor, and recovered thousands of rounds of the 12.7mm ADMG, 60mm mortar, scores of gas masks, and containers that may have contained chemical content.

We launched the attack on Khalubar on July 2 with about 250 soldiers. However, by July 8 at Point 5287, we were down to about 36 due to the battle, weather, and severe poisoning from gunpowder-contaminated snow water.

Munthu Dhalo

On July 8, from Point 5287, we observed intense enemy activity on the watershed along the Line of Control (LC). It seemed the enemy troops were withdrawing from various locations, possibly consolidating for a last-ditch stand to retain control of the LC. Additionally, there was a lot of activity in the Munthu Dhalo bowl. Time was critical, so we decided to race for the LC instead of reverting to Yaldor after completing our assigned task.

Our first objective on July 9/10 was Point 5190, which completely dominated the Munthu Dhalo Bowl. All enemy ingress routes passed through Munthu Dhalo, where their logistics base was located. Next was Point 5300, on the LC and the watershed itself. Finally, on July 26, our attacks culminated in the capture of an inconspicuous but critical post called Tekri on the LC. A ceasefire was declared in the morning just as I flew the Tricolour at Tekri on the LC.

From Tekri (adjacent to Point 5300), we saw hundreds of enemy soldiers running in panic towards the west. We could pick them off one by one with ease. The panic and disorganisation in the enemy camp were complete. At this point, I felt we were very strong in terms of units and formations, with immense artillery and engineer support. It was my personal estimate that we could have crossed over and undertaken further offensive operations, potentially cutting off their access routes to their part of the Siachen Glacier.

Reflections

The 80 days in combat were a humbling experience. We owe our sterling performance to the brave soldiers, young officers like Captain Manoj Pandey, leaders like Colonel Lalit Rai, VrC, our superlative Commander, Brig Devinder Singh, his energetic BM, Maj Inderbalan as well as the DQ, the immense support from the artillery, and officers like Major Vinay Dutta, who organized the porters, an essential battle-winning factor.

Fighting the Same War 25 Years Later

A large-scale incursion into Indian territory is expected to be avoided due to advanced surveillance means across various domains – satellite, air, drones, cyber, electromagnetic spectrum, human intelligence, and a comprehensive intelligence setup, along with a more capable and alert military on the ground.

The Kargil operations provided the Indian Army with an opportunity to launch offensive actions, albeit limited to within our own territory. In a full-scale war, it will be necessary to penetrate deep into enemy territory. This requires that the entire military apparatus – command, control, information, intelligence, surveillance, communications, logistics, fire support – must extend beyond our established networks into essentially hostile territory. This is a critical factor we need to prepare for.

In the current context, what are the advantages or changes with respect to Operation Vijay? We can briefly address each one.

- Combat Logistics: In offensive operations in hostile mountainous territories, roads and tracks may only be available up to a point. Beyond that, logistics for infantry may rely solely on man-pack and animal transport for a considerable time. Therefore, planning the sustainance of offensive infantry is crucial. In 1999, local porters and their “Small Donkeys” (SD) were the backbone of logistics beyond the road head. Currently, this support has likely dwindled sharply due to the thinning out of border villages, higher education, and employment of the younger generation in distant cities, and possibly decreased physical fitness. The number of SDs has decreased sharply due to better road networks to forward areas and a consequent drop in demand. Therefore, in case of an offensive operation, despite raising Pioneer Companies, we might face a significant challenge in logistic support traditionally provided by the local populace and AT.

- Infantry Tactics: Future wars might involve offensive operations in rugged, high-altitude, road-less mountains across the Line of Control (LC) and thus in hostile terrain. These operations would primarily be infantry-oriented. Certain tenets of offensive infantry tactics can be explored, such as relentless offensive action, outflanking, masking, and containing hard enemy locations while maintaining the pace of the offensive. Building up substantial forces at key decision points behind the enemy frontline is critical for early success. Seizing targets deep within enemy territory by aerial insertion could be very effective, with aerial extrication being equally crucial. Concepts of encirclement, isolation, and investment need to be explored and matured through realistic training exercises.

The above concepts would likely be adopted at the micro level as well, depending on the situation. The emerging scenario might see the intense application of various drones for kinetic attacks and battlefield transparency, although current capabilities are still developing.

- Kinetic Weapons: Upgrades in small arms may include better assault rifles (Sig 716), Negev LMGs, and SAKO Sniper Rifles. These upgrades offer advantages in firepower for close battles. Ensuring the best use of these weapons requires thorough training, an adequate number of weapons, and the availability of optical sights. This also applies to multi-mode hand grenades, MGLs, AGLs, and other weapons. Adequate ammunition is critical in combat.

Similarly, high precision artillery munitions and the benefits of such technology in rugged mountain terrain need to be considered.

Similarly, high precision artillery munitions and the benefits of such technology in rugged mountain terrain need to be considered.

- Military Robotics on the Battlefield: Current drones are many generations behind those of our potential adversaries. In the infantry context, drones and robotics are new tools with minimal presence. They are effective in environments without countermeasures and turbulence. In a war situation, we must prepare for possible countermeasures, including hard/soft kill, hostile drones, and hostile domination of the electromagnetic spectrum. We also need to account for our own turbulence, which includes power supply disruptions, logistic challenges, new tasks and demands of offensive operations, and new operating methodologies. Turbulence also involves the need for maps/Coordinates, rapid and frequent crew turnover. Without these challenges and in the absence of hostile countermeasures, these force multipliers have proven somewhat useful, as seen in recent incidents in the Jammu Sector.

Communication and Unit Cohesiveness: Communication posed a significant challenge in the rugged mountains of the Batalik Sector. The primary issue was the ineffectiveness of the radio equipment—VA Mark 2 and VPS often proved useless.

The challenges included:

- Rechargeable Batteries: The radios only used rechargeable batteries, but there was no way to recharge them except at the road head, which was days away. Used batteries had to be sent down to the road head on foot, charged over a day, brought back, and redistributed to dispersed locations.

- Limited Frequencies: The limited inter-communicable frequencies with the backbone network of ANPRC radio sets required more screening. Additionally, the inability to reset new operating frequencies due to the need for specific equipment meant all units in the sector had to operate on very few frequencies.

These issues can be mitigated with modern Software Defined Radios and Mesh Networks. However, the challenge of recharging batteries in offensive mountain operations persists since new generation equipment also relies solely on rechargeable batteries.

- Battlefield Transparency: Modern day and night vision equipment, sensors, drone-based multi-spectral feeds, and possible feeds from higher headquarters could significantly enhance troops’ capabilities in contact. Additionally, intense training is required to ensure proficient handling.

- Battlefield Mobility: In the mountains, mobility will continue to be on foot. Currently, few higher mobility platforms are available to front line infantry. Mobility based on such vehicles would be limited to tracks on our side of the watershed. Regaining mobility across hostile terrain would be challenging, making infantry movement and logistics reliant on foot and animal transport for the initial days or weeks. If properly implemented, drones could provide limited front-line logistics in contact battles, although such capability is currently in its early stages.

- Survivability: There have been significant advancements in battlefield first aid and medication, improving the chances of saving the wounded with better first aid available to soldiers and forward troops. The availability of forward medical care has also improved, along with the means of casualty evacuation from the road head or rear areas due to better helicopter access and all-terrain vehicles. Improved first aid kits have yet to reach front line soldiers, and they need training on using these life-saving kits.

Body armour, in the form of bulletproof jackets, has been introduced. However, in high altitudes and rugged mountains, a 10 kg bulletproof jacket can become a burden. During Operation Vijay in 1999, we recovered khaki-colored BPJs of UK origin at Khalubar and Point 5287, but no soldier was wearing one, indicating the impracticality.

- Manpower Aspects: The infantry section must be organic and trained as a cohesive team to perform effectively in combat. This requirement extends to the platoon, company, and battalion levels. Troops must be adept, daring, and indefatigable in mountainous terrain, necessitating intense sub-unit level training. Combat support weapons such as the LMG, MGL, RL, 51mm Mortar, sniper rifles, MMG, and AGL are invaluable. The performance of a seasoned, experienced, and thoroughly trained crew in combat is a battle-winning factor.

However, realistic training is hampered by shortages of manpower, severe lack of training ammunition (like MGL, AGL, UBGL, ATGM, sniper ammunition, etc.), lack of ranges, and limited opportunities for intense training. In combat, it is common to find that the soldier trained for a particular weapon may be injured, killed, or reassigned, causing the weapon to fall to another soldier. Therefore, it is critical for every soldier to be capable of using every weapon effectively.

Soldier Kit: The infantry section, platoon, and company need appropriate ‘kit’ to fight effectively. Basic needs include drinking water (water bottle), the ability to melt snow/ice for drinking (metal water bottle), an enamel mug (for drinking, heating, making tea, or even cooking rice), a robust ‘mess-tin’, a comfortable haversack, a large backpack, a rain-proof cape, good breathable boots, and comfortable cotton combat dress suited to the combat zone.

We found that the ‘kit’ has suffered badly. Soldiers are compelled to carry water in plastic bottles, the enamel mug has been replaced with an ineffective one, and the ICK design is flawed and grossly inappropriate. The section or platoon lacks appropriate containers to carry water from the source to the troops. The introduction of ‘Meals Ready to Eat’ has not yet matured and may have diluted traditional ‘soldier foods’ that worked well in the past. There are many such ‘real’ aspects that need to be fixed to enable soldiers to perform in sustained offensive combat.

In conclusion, one can safely state that as a responsible and professional Army, we must expect, anticipate, equip, prepare and soundly defeat a misadventure by any adversary.