Articles

DAP Revision: Shifting from process Centricity to Capability Centricity

Sub Title : Rewiring India’s defence acquisition: urgent tweaks and actionable recommendations

Issues Details : Vol 19 Issue 4 Sep – Oct 2025

Author : Lt Gen NB Singh

Page No. : 36

Category : Military Affairs

: September 23, 2025

The Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP), while intended to streamline and standardize acquisitions, has in practice made the process more complex, rigid, and time-consuming. Several years after its introduction, the DPP was re-branded as DAQ, possibly after realising that acquisition is different from procurement. Procurement is a short term exercise that entails buying a ready made product like clothing and general stores using a pre – defined procedure. Defence acquisition on the other hand is long term, ideally aiming to acquire strategic capabilities viz; an operational capability, an industrial/ technological capability and a through life support capability(MRO). Since acquisition aims to develop national capabilities, be it operational , technological and industrial, it needs to be a flexible adaptive process that is mission oriented instead of a process orientation. Para 29 (ii) Chapter 1 of DAP 2020 talks of process integrity in Chapter 1 itself and hence this issue resonates as the core philosophy throughout all chapters of DAP.

Procedure vs Guidelines

Aspect Procedure Guidelines

Prescriptive Mandatory, rigid sequence of steps Flexible, advisory, adaptable

Legal binding Often binding and enforced strictly Generally non-binding, discretionary

Suitability Works well for standardized processes Suited to complex, evolving environments

Bureaucratic burden Higher, with formal approvals at every step Lower, focused on outcomes

Calling it a “procedure” reinforces rigidity, while “guidelines” allow for context-based flexibility.

Complexity and Procedural Overload in the Current DAP

Many defence experts and stakeholders have observed that :-

- Procurement timelines stretch over years due to layers of approvals, evaluations, trials, and committees.

- The sheer volume of documentation and compliance (e.g., Technical Oversight Committees, Cost Negotiation Committees) delays critical acquisitions.

- The system prioritizes process compliance over strategic outcomes — a “tick-box” culture.

- Despite procedural safeguards, delays often result in cost escalation, obsolescence or capability gaps.

The current form may be over-engineered, especially for routine or low-value procurements. It may be a good idea to rename DAP as the Defence Acquisition Guidelines (DAG). If most other Ministries can carry out procurement using the standard General Financial Rules (GFR), MoD too can do so. Before advent of DAP in 2002, many big ticket items were procured by MoD using the GFR. DAP since its inception has made acquisition of defence equipment complex, rigid and time consuming; the consequence of which is that by the time an acquisition take place, obsolescence of the platform has set in, in the country of origin. Each revision has only added additional pages and binding provisions that repeatedly stymie flexibility and a mission mode approach.

Guidelines Based Framework

A rigid “procedure” cannot easily accommodate such dynamism — a guidelines-based framework could allow the MoD and armed forces to adapt more swiftly. DAP needs to graduate to DAG specially now when the country has realised the vulnerabilities of foreign supply chains . If a disruption/ slow down in supply of rare earths, chips, EV accessories can cause industrial slow down, imagine what a disruption in supply of aero engines, marine gas turbines, sensors and munitions could do in war time. From an import or build on TOT and maintain philosophy the country has to graduate to a design, develop, manufacture and sustain philosophy. This cannot be done through an accountant`s approach to defence acquisitions. It requires an Engineer`s approach, that focusses on core issue of achieving genuine self reliance, of building weapon platforms that provide operational overreach and sustained competitive advantage. Frauds and corruption issues can be addressed through an appropriate whistle blower policy rather than using a very tight jacketed procedure that inhibits discretion, actions in good faith and accepts huge delays just to get the process right. Most of the time when acquisitions see the light of the day, the weapon platforms being inducted have or are entering obsolescence. US DoD follows the Defence Acquisition System, which provides guiding principles and flexibility to Program Managers based on the type of acquisition.UK MoD uses an approach based on Smart Acquisition Principles, emphasizing flexibility, risk-based planning, and project-specific tailoring.

Procedural Rigour

Before DAP, big deals often relied on direct negotiations, political approvals, or inter-governmental agreements (IGAs).The GFR offered flexibility, with a focus on financial prudence but less procedural layering. After DAP, procurement became a multi-stage, standardized, committee-based process. The time taken from need identification to contract signing has increased exponentially, especially for capital acquisitions.

- Over-Engineering of Process. DAP was designed with the intent to avoid corruption scandals (e.g. Bofors), but it led to risk aversion among bureaucrats. File movement slowed due to fear of vigilance and audit scrutiny. Preference was for procedural correctness over timely decision-making. Outcome was that delays became systemic, not exceptional.

- One-Size-Fits-All Model. DAP applies similar procedures to all acquisition types, whether buying a few drones, leasing aircraft or acquiring platforms like submarines or modernising a MRO set up. This “template-based” approach has created bureaucratic bloat even for relatively simple procurements. In contrast, under GFR, ministries could adapt procurement routes to suit operational urgency or strategic needs.

Make In India

The kernel of revision of DAP, two decades after its introduction has to be directed towards bringing to fruition genuine self-reliance , not procedural rigour. If Make in India has to genuinely succeed, defence acquisition has to facilitate creation of a local defence industrial base (DIB) comprising system integrators, sub system houses, component manufacturers, design houses, anchor institutions, etc. Hence, where feasible a genuine IDDM product must be give higher credits as compared to a foreign system assembled locally and fielded for trials by an indigenous player with the aim of assembling the same in India . K9 is an example, MGS could follow suit. K9 is being assembled in India by a leading SI but one needs to look deeper to the extent of local industrial capabilities created to guarantee operational resilience and strategic assurance to the military over its life cycle of approximately 40 years. One hopes it is not a repeat of what the DPSUs have been doing for the past 3-4 decades where critical import dependencies remain. It may have been better to incentivise the foreign OEM to operate locally using the gearing offered by a requirement of 200 to 300 platforms. Imagine the pace of industrial activities in the DIB specially MSMEs if over 90% of the parts of K9s were indigenously produced by now.

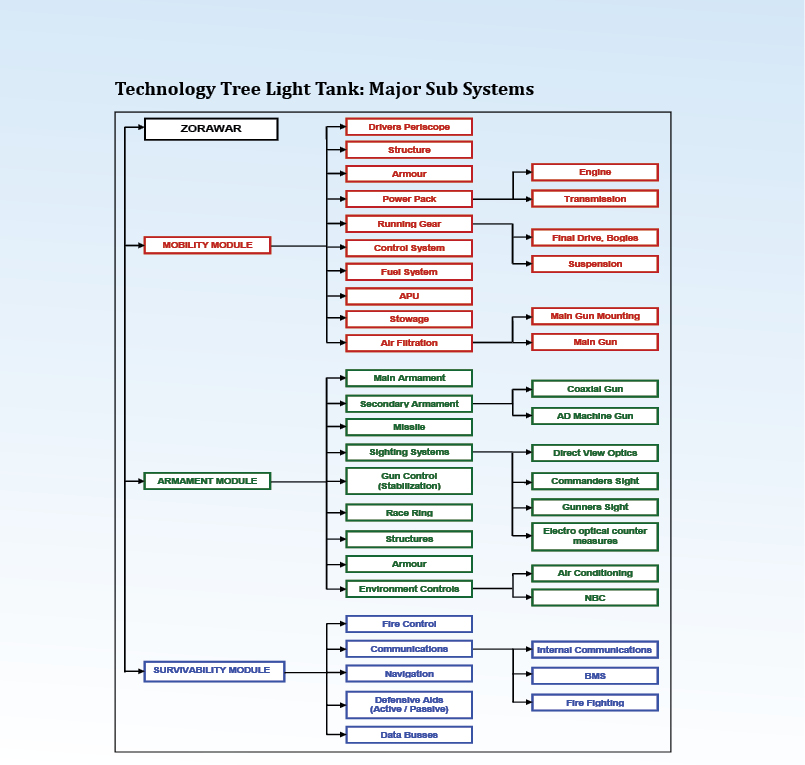

I recommend a technology tree approach being essential to realise the dream of genuine self reliance. Take the case of light tank. Assuming that the light tank currently under trial gets accepted by the Army. As is reported, it has been assembled majorly using foreign sub systems to the extent of 95 % or more , despite the stipulations of IC. Only the steel appears to be indigenous. What should be the way forward to complete this acquisition if the tank comes out a winner after the ongoing trials. A logical approach would be to create an EOQ to facilitate self-reliance. Instead of the order of 59 tanks that has been set aside for Zorawar, the entire requirements of 354 tanks should be clubbed into one order to facilitate local manufacture. In fact, the numbers can be scaled up to over 500 platforms by clubbing the requirements of amphibious dozers, AD carriers, recovery vehicles, etc. The DAP needs to contain enabling provisions to allow such a switch. An image and a technology tree of the light tank is given below. The image shows the impressive overall architecting of the tank. The technology tree shows the large no of sub systems and sub-sub systems (40 approx) that are needed to integrate a tank and make it deliver an operational capability.

The new DAP/DAG should provide enough flexibility to enable the Project Manager to indigenise as many subsystems as possible and as soon as possible. The engine and transmission manufacturer may get incentivised to go in for full indigenisation if the EOQ is there. In case of MBT Arjun, had the Govt taken a call to manufacture more than 300 tanks ab initio, the 1400 hp power pack would have been indigenised decades back ,thus obviating the current stalemate in proceeding with the manufacture of 114 Arjun tanks. Today the cost of an Arjun power pack is upwards of 40 crores. Enough discretion needs to be inbuilt in the DAP, with the belief that the acquisition community under the leadership of RM is acting in good faith for the nation`s well being. One need not shackle the acquisition wing with complex , straight jacketed procedures that inhibit adaptability and agility simply because one is apprehensive of a financial fraud or corruption . A sound whistle blower policy with incentives could instead help inhibit corruption more effectively in the era of digital trails .

One can reduce import dependencies not by replacing foreign companies ( an ideal aspiration for self reliance) but by making them operate locally rather than exporting. This can happen if foreign companies manufacture to meet local demands.

Flexibility and Agility

Some other initiatives that can introduce agility and flexibility are as under:-

- Qualitative Requirements or System Requirements need to be configured as a capability development document and not as a complex attribute centric paper exercise , gold plated by cut pasting attributes of foreign systems. Mission engineering has always been overlooked in our GSQRs ; as a result immediately after induction of a platform, operational capability gaps begin to surface. The platform is either not suitable for deployment in a specific terrain, or it fails to operate above a certain altitude in mountains or it does not give the performance claimed by the foreign OEMs. A chapter containing guidelines to frame QRs would be an enabling step.

- L1 Procurement Approach. It has to be realised that in most cases this approach leads to the acquisition of low cost -low effectiveness system that is characterised by low readiness rates, high downtimes and high operations and support cost over the life cycle. Instead, a 95% solution approach that balances performance, cost and time lines in the best possible way, could be adopted. A full T1 approach may lead to a fully loaded system, so called wunder waffe that lacks system maturity and its complexity could become difficult to sustain over the life cycle . The DAP has to be adaptable enough to allow such trade-offs.

- IC Content. Para 21 by stipulating IC content by cost defeats the whole intent of Make in India. It is for this reason that fighters, warships and tanks built in India have huge foreign dependencies over the life cycle and hence low readiness rates. How can one claim self sufficiency in ammunition of a certain type when the propellant, explosives and fuses continue to be imported cheaply from certain East European countries? Same is with dependencies of propulsion systems, sensors and armaments. It is important that a major course correction is done by stipulating that most foundational systems should be manufactured in India with maximum ( 90% over a period of time ) components sourced from local MSMEs.

- Manufacturing Delusion. The current approach to acquisition of IDDM platforms is delusionary. A deeper look will reveal that in most cases of prototyping , it is more an assemblage of proven or available or obsolescent foreign sub systems integrated locally to give a specific level of performance. MBT Arjun, Tejas, Light tank, air defence ship, most indigenous naval platforms all fall in this category. Post successful evaluation, cost based IC ensures that crucial foundational systems remain on import list due to high cost of indigenisation. A mandatory stipulation in QRs that self sufficiency in generic and foundational systems is non negotiable , is needed to make the requirement of genuine localisation come to fruition. Since such technologies are not available, Govt funded programmes need to be initiated using a mid to long term strategy; like initial manufacture of say 50 to 100 LCAs to be done using imported aero engines followed by an engine made in India; either locally developed or manufactured in concert with foreign OEM operating for local requirements. Foreign companies need to be incentivised to localise production to further the goal of embedding domestic supply chains.

- Revisit of Categories of Acquisition. The categories of Acquisition need to be reduced to the minimum say three; Made in India designed and developed indigenously, using local brain power and embedded supply chains; Made in India by foreign OEM ( singularly or through JV) using a mixed supply chain and Acquire Global through Govt to Govt/ OEM to Local Company route with partial localisation of supply chain using offsets. A supply chain focus is important to rev up the manufacturing sector and ensure strategic assurance and resilience. If this measure is not strictly implemented even our exports will get impacted in the mid term, when nations operating our platforms realise that for critical sub systems of a missile or rocket platform or a ship , they have to approach another country for technical support.

- Agile Procurement Pathways. Centralization under DAP has led to more control and less agility. Time to consider the following:-

o Fast-track for emergency buys.

o Sandbox models for new tech.

o Simplified path for indigenously developed systems.

Pros of Shifting to “Defence Acquisition Guidelines. It allows for greater flexibility by tailoring based on value, urgency, or strategic need. Leads to faster decision-making by reducing delays caused by rigid sequencing. It encourages innovation making it easier to adopt new technologies or procurement models. Can lead to better industry engagement specially with start ups, MSMEs, and foreign OEMs by simplifying rules . A simple example is the stipulation of expanding the vendor base once an item has been indigenised. This has led to corruption and deteriorating quality , instead what is needed is guaranteed buy back for 10 years or so if a MSME has successfully indigenised an item. This how industry can be engaged positively to serve national interest. An outcome oriented focus that shifts the mindset from “process adherence” to “capability acquisition’’ is indispensable.

Risks and Challenges. Guidelines may be seen as less stringent, raising concerns about transparency or corruption. Without firm procedures, different acquisition teams might apply rules inconsistently. It could lead to accountability issues as officials may hesitate to take bold decisions if there’s ambiguity in guidelines. Institutional memory can come in handy and hence the need for longer tenures.

Hybrid Model

Introduction of a tiered acquisition model — rigid procedures for high-value or sensitive procurements; flexible guidelines for low-value or time-sensitive acquisitions could be a step forward. One could look at retaining DAP as a base policy, but structure it into a Core Mandatory Procedure (for strategic, capital-intensive deals) and Flexible Acquisition Guidelines for urgent, low-value or tech- acquisition / foundational systems related buys. Even for upgrades of legacy systems and modernisation of MRO assets a flexible approach is recommended to fix capability gaps and develop local supply chains.

Conclusion

The criticism that DAP is too complex and rigid is valid in many cases. Moving toward a guideline-based or hybrid framework could make defence procurement more responsive, efficient, and outcome-driven. Renaming it as “Defence Acquisition Guidelines” or “Framework” is not just cosmetic — it could reflect a philosophical shift from process-centricity to capability-centricity, so essential to incubate national resilience and strategic assurance as the war in Ukraine has repeatedly shown.

Lt Gen (Dr) N B Singh, PVSM, AVSM, VSM, ADC is a former DGEME, DGIS and Member Armed Forces Tribunal. Views expressed are his own.