Articles

Nepal

Sub Title : How a platform order lit a youth uprising, toppled a government, and reset South Asia’s border, energy, and digital equations

Issues Details : Vol 19 Issue 4 Sep – Oct 2025

Author : Ashwani Sharma, Editor-in-Chief

Page No. : 20

Category : Geostrategy

: September 23, 2025

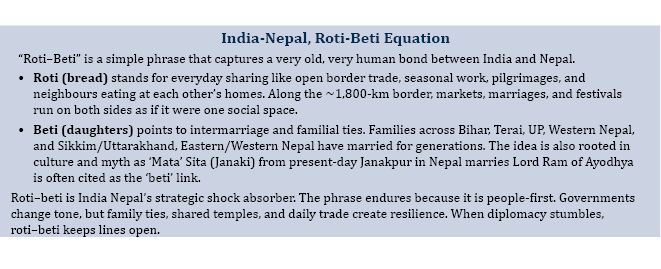

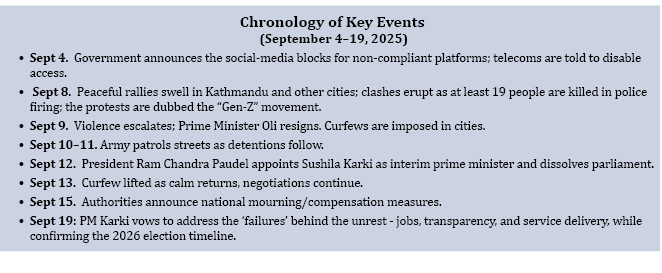

Nepal’s week of upheaval began with a decision that appeared to be technical, in that, a plan to block social-media platforms that had not registered locally. But it quickly exposed something deeper – a generation’s anger at corruption, unemployment, and a state that felt unresponsive. As the street energy surged, the government fell (see the Timeline box), and an interim administration under a respected jurist stepped in to calm tempers and promise elections. That chain of events, though rooted in Kathmandu, radiates across South Asia in a number of ways which are both practical and strategic.

For India, the first ripple is always at the border. The India – Nepal frontier is open, intimate and busy; when politics wobbles in Kathmandu, truck lines become longer at Raxaul-Birgunj and other crossings, fuel deliveries get irregular, and prices fluctuate on both sides. Stability matters not only for trade in essentials, but for power cooperation. India’s long-horizon bet is that Nepal’s rivers will always continue to light homes across the region; any prolonged disorder complicates dam timelines, grid agreements, insurance, and financing. Delhi and Kathmandu have a long-horizon plan for Nepal to sell up to 10,000 MW to India over the next decade. Prolonged instability would ruin timelines and financing, while stability can accelerate investments and grid work.

If the interim government can restore predictable administration, the energy corridor will keep moving; if not, planners in India will be left facing delays and premiums.

The second obvious ripple is digital policy. Nepal did not try to erase the internet. It asked platforms to register and appoint grievance contacts. Yet the rollout, perceived as a gag order, became the spark. Every capital in the neighbourhood is watching. Governments want accountability from big platforms; whereas citizens fear censorship by stealth. What Kathmandu does next by way of clearer rules, transparent appeals and published audits, could become a regional template. A heavy hand will restrict speech and invite a pushback, a rules-first, rights-aware approach could show how to regulate without silencing.

Third, there is the China-India balance in the Himalayas. Beijing has courted Nepal with connectivity and investment; Delhi’s advantage is proximity, people-to-people links, and energy trade. In moments of flux, both sides move quietly. China to protect project pipelines and security equities; India to keep borders and fuel flowing, and hydropower on schedule. An interim, non-partisan government gives everyone breathing room, but the contest is not zero-sum. If Kathmandu plays its cards well, it can run a clever policy, accepting quality investment and connectivity from all sides while keeping sovereignty and transparency intact.

Fourth comes economics beyond the border posts by way of tourism, remittances, and credits. Nepal’s high season depends on a sense of safety; even a short period of violence dents bookings and small-business cash flows. Lenders and rating agencies, already cautious in a tougher global environment, will scan for signals like curfews lifted, schools open, compensation delivered, rules clarified. Quick administrative wins will matter here: cleaner procurement, visible action on graft cases, and a credible election calendar are worth as much as any speech.

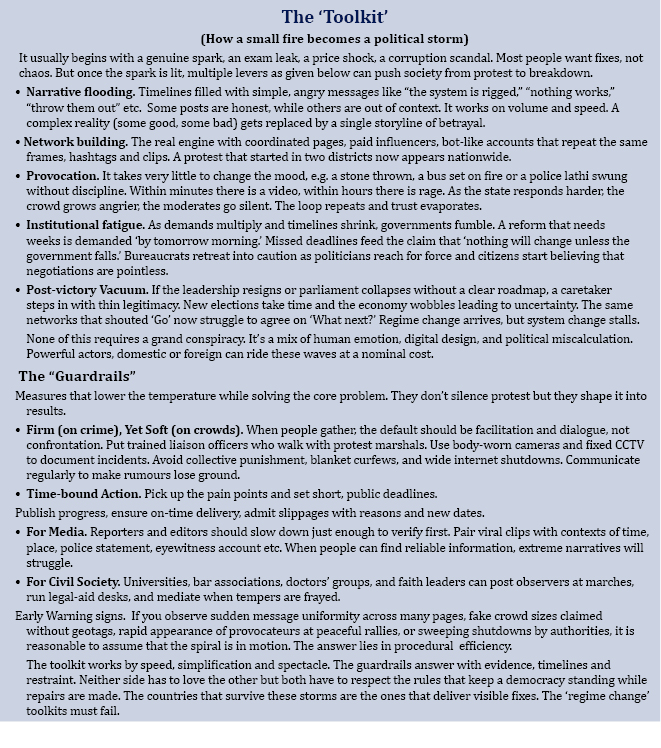

The fifth ripple is likely to be political. Bangladesh’s recent campus-led churn showed how student networks, economic stress, and digital issues can combine. Nepal adds a new lesson to this, that when governments treat connectivity as a switch, they risk uniting fragmented grievances into one united wave. That does not mean states must surrender the field to disinformation or hate speech; it means the cure cannot look worse than the disease.

Finally, there is a quieter but important effect on regional connectivity. The BBIN (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal) road protocols, cross-border rail, and power-trade frameworks all thrive on predictability. A Nepal that steadies itself can unlock cheaper logistics from the Gangetic plain to the Himalayan foothills, give Indian exporters confidence, and offer China and other partners space to compete on transparent terms. A Nepal that slips back into rolling crisis forces everyone into hedging mode implying shorter contracts, higher costs, and slower execution.

Lessons from the Region

Across South Asia, big crowds have forced big changes in recent times.

Sri Lanka (2022) was the earlier signal as a people’s movement called Aragalaya which toppled a powerful presidency amid shortages and economic collapse. The president fled, but the economic and governance grind persisted, reminding everyone that regime change is not the same as system change.

Bangladesh (2024), student protests over job quotas grew into a nationwide uprising; Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina resigned and left the country after weeks of deadly clashes. Independent tallies put the death toll in the hundreds, with mass arrests and curfews as the state struggled to regain control.

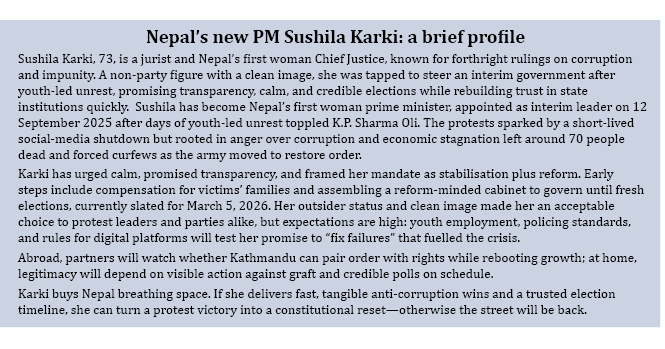

Nepal (2025) now faces its own inflection point. Youth-led anger, sparked by a social-media ban and long-standing complaints about corruption and joblessness turned violent in Kathmandu; Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli resigned and reversed the ban, with soldiers on the streets. The pattern rhymes – focussed grievance, rapid mobilisation, state overreach, and then political collapse.

In Nepal, the story is not yet finished. The interim leadership has promised calm, justice for those killed, and an election road map. If those promises are kept, India gains a stronger, more predictable neighbour and a useful case study in governing the digital public square. If they are not, the street may return, and with it the usual chaos and costs by way of lost time, lost money, and frayed trust.

This moment can be turned into a regional dividend. India should move first on practical fixes like border facilitation and power/energy timelines, while keeping politics low-key, yet practical. China will attempt to keep projects going and appear non-coercive. And Kathmandu should convert protest energy into institution-building for clean procurement, clear rules, and an election date which no one doubts. The Himalayas must become a bridge again and not a fault line.

Nepal’s Gen-Z Uprising

Nepal’s new wave of youth protests was more than a burst of street energy. It was a generational verdict on three things simultaneously – (i) jobs that don’t exist, (ii) public services that don’t work, and (iii) politics that refuses to change. The agitation has spread from campuses and coaching centres to town squares and the digital feeds that shape daily life. Whether it becomes a true “revolution” or pushes the system toward reforms will depend on how quickly the state fixes everyday failures and how smartly the movement avoids co-option.

The protests in Nepal began after the government announced that major social-media platforms must register locally and set up grievance contacts, or be blocked. Many young people read this as a new restriction on communication. Student groups in Kathmandu were the first to organise meetings near campuses and public squares. Early gatherings were mostly orderly, with brief speeches and placards describing the demand: withdraw the blocking order and open a wider discussion on transparency and jobs.

As access to some apps became unreliable, students and workers shifted to whatever channels still functioned—SMS, email lists, smaller messaging apps, and word of mouth. Class representatives and alumni networks shared times and locations. Within a short time, several spots around the capital saw parallel assemblies. Police presence increased. In a few locations, scuffles occurred at barricades and tear gas was used; in others, marchers followed police directions and dispersed on time. Videos and text updates moved between cities, helping others plan their own meetings.

The movement then spread along regular travel routes. Students who went home for the weekend or a holiday carried the issue to their towns. Cities such as Pokhara, Biratnagar, Nepalgunj, Butwal, and Bharatpur reported rallies of varying size. Local civil society groups like lawyers’ forums, teachers’ unions, health workers’ associations offered logistical help such as legal hotlines, first-aid desks, and liaison with district officials. In a few districts, curfews were imposed for limited hours; elsewhere, authorities used sectioned traffic controls to keep main roads open.

Workdays became quieter in commercial centres. Public transport services were reduced on some routes, either by order or because drivers stayed away. Government offices functioned but with lower attendance. Funeral gatherings for those who died in early clashes drew large participation and acted as focal points for peaceful marches the next day. Community leaders like religious figures, ward chiefs, retired teachers etc encouraged calm and asked both police and protesters to avoid confrontation.

Coordination gradually became more structured. Organisers issued simple guidance to stay off hospital roads, avoid government schools during exam hours, and keep rallies within notified time windows. District administrations opened more help desks and began publishing clarifications on movement restrictions. Media houses and fact-checking groups tried to verify circulating claims, which reduced confusion in some cases.

Violence the Ugly side of Protests

Most participants remained peaceful, however, incidents of arson, assault and vandalism by some protesters, and force including live fire in hotspots by security units caused heavy casualties and mistrust.

Some protesters set buses and municipal offices ablaze, vandalised party buildings and toll booths, hurled stones and petrol bombs, and assaulted police and bystanders. Within 24–48 hours, mobs set fire to leaders’ homes and offices, including the PM’s private residence and assaulted some politicians. Local media and wires reported attacks on the houses of ministers such as Prithvi Subba Gurung and stone-pelting at Finance Minister Bishnu Paudel’s residence; several senior leaders, including ex-PM Sher Bahadur Deuba and Arzu Rana Deuba, were also attacked, with evacuations by helicopter from some sites.

In response, security forces used batons, tear gas and, in several hotspots, live fire, worsening casualties and mistrust. Curfews shut markets, interrupted fuel and medicine supplies, and stranded travellers. The agenda of reform was overshadowed by fear and damage and slowed recovery.

Political effects followed thereafter. Several parties issued statements supporting the right to protest while urging talks. Business associations asked for a timeline to restore normal commerce. After a couple of days of unrest and rising pressure, PM Oli resigned. An interim government led by a non-party former chief justice has now taken office with a limited mandate to maintain order, compensate affected families, review the platform policy, and prepare for elections. Curfews were lifted in most places, schools reopened, and traffic returned, though weekend rallies continued at a smaller scale.

Overall, the protests spread because a policy seen as limiting communication met existing concerns about governance and jobs. Movement relied on ordinary networks like campuses, alumni groups, professional.