Articles

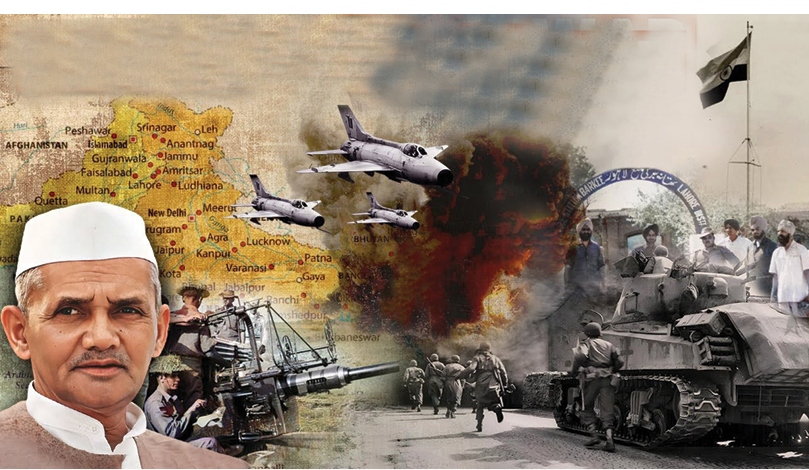

The 1965 Indo-Pak War

Sub Title : Preamble to the 1965 Indo Pak War

Issues Details : Vol 19 Issue 3 Jul – Aug 2025

Author : Ashwani Kumar, Editor-in-Chief

Page No. : 15

Category : Geostrategy

: July 29, 2025

In the turbulent decades following Independence, South Asia’s security landscape was marked by distrust, partition trauma, and clashing national ideologies. The 1965 Indo-Pak war, often overshadowed by the wars of 1947–48 and 1971, deserves greater attention, not merely for the military contest it became, but for the dangerous miscalculations, faulty geopolitical assumptions, and flawed strategic overreach that Pakistan brought to the table. From India’s point of view, the conflict was a classic case of deterrence being tested, and of national resolve rising beyond expectation.

Geopolitics Before the 1965 Indo-Pak War

By the early 1960s, the geopolitical landscape of South Asia was marked by volatility, ambition, and a profound recalibration of strategic alignments. The region was still in the early years of post-colonial statehood, and both India and Pakistan were navigating their emerging national identities amid a rapidly evolving global order defined by Cold War rivalries.

India was undergoing a painful yet necessary period of self-reassessment. The 1962 war with China had dealt a severe blow not just to India’s military standing, but also to its global image. The loss in the Himalayas exposed grave deficiencies in India’s defence preparedness, intelligence assessment, and political-military coordination. Internationally, it undermined India’s image as a regional power; domestically, it shattered the illusion that moral posturing and diplomacy alone could guarantee peace.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, whose foreign policy had long been rooted in non-alignment and anti-imperialist solidarity, was visibly shaken by the conflict. The 1962 war marked the beginning of the end of Nehruvian idealism, with a gradual transition toward realism and rearmament. By the time Lal Bahadur Shastri took office in 1964, India was actively rebuilding its defence capabilities, modernising its armed forces, and forging closer ties with the Soviet Union for strategic balance.

Economically, India was still constrained. The Second Five-Year Plan had overreached in terms of industrial ambition, and agricultural production was under pressure. Defence expenditure was being ramped up, but the process of consolidation would take years. Militarily, the Indian Army was in transition; it was re-equipping, restructuring, and most importantly, restoring its morale.

Pakistan’s Ambition and Miscalculation

Across the border, Pakistan under Field Marshal Ayub Khan was charting a very different course. A military dictator who had seized power in 1958, Ayub was determined to position Pakistan as a modern, disciplined, and strategically relevant nation aligned with Western interests. His foreign policy leaned heavily on the Cold War alliance system, and he secured Pakistan’s place in two major US.- backed military groupings viz, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO).

These alliances yielded significant returns. The United States and the United Kingdom supplied Pakistan with large quantities of advanced military hardware including M48 Patton tanks, F-86 Sabre jets, and sophisticated artillery systems. On paper, this made the Pakistan Army and Air Force appear more capable than India’s, particularly as India was still reliant on a mix of British and Soviet-origin equipment, much of which was ageing. This perceived military edge bred a dangerous sense of overconfidence in Rawalpindi. The Pakistani military establishment, buoyed by Western patronage and the illusion of conventional superiority, began to seriously consider military solutions to what it viewed as the unfinished business of Kashmir, the ‘jugular vein(!)’ of Pakistan.

Internal Pressures and the Kashmir Obsession. By the early 1960s, Ayub Khan’s domestic standing was eroding. His “Decade of Development” slogan was losing traction among the public, with rising discontent over inflation, political suppression, and elite-driven governance. The press was controlled, opposition silenced, and democratic space increasingly curtailed.

In such a scenario, the externalisation of internal crises became a natural path. Kashmir provided the perfect rallying cry. Not only was it emotionally and ideologically potent for the Pakistani populace, it also offered a way for Ayub to galvanise national sentiment and deflect attention from domestic fissures.

Thus, the geopolitical climate before 1965 was defined by asymmetrical perceptions. While India was consolidating, cautious, and internally focused, Pakistan was ambitious, externally postured, and increasingly aggressive in outlook.

Pakistan’s Decision to Go to War. Pakistan’s decision to initiate war in 1965 was based on a dangerous cocktail of overconfidence, miscalculation, and flawed intelligence.

- Perception of Indian Weakness. The 1962 war with China was misread by Pakistani strategists as proof of India’s incapacity to fight. They believed the Indian Army had low morale and lacked modern equipment, unaware that India had undertaken serious reforms and rearmament post-1962.

- Internal Dynamics. Ayub Khan sought to bolster his political legitimacy. A military victory, particularly one that “liberated” Kashmir, would shore up his popularity.

- International Context. The Cold War was in full swing. Pakistan felt protected under the US umbrella and believed any Indian escalation would be diplomatically constrained. China was also viewed as a potential pressure point against India.

- Misreading Kashmir. The belief that Kashmiris would rise in revolt against India if Pakistani forces entered was a critical error. Pakistan’s plan ‘Operation Gibraltar’ was designed around this assumption.

Pakistan’s Domestic Political Pressures. Internally, Ayub Khan was facing growing unrest. His authoritarian model was beginning to show cracks. Political opposition was stirring, particularly in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and civil society was increasingly uneasy with the centralised, elitist governance model. Ayub’s popularity, once formidable, was in decline. A swift military victory in Kashmir, especially one portrayed as the liberation of fellow Muslims under Indian “occupation”, was seen as a politically rejuvenating gambit. Victory in Kashmir would bolster Ayub’s image, reassert Pakistan’s claim over the region, and silence domestic critics at least temporarily.

This pressure to act, coupled with a distorted sense of military superiority created a sense of strategic opportunity, albeit based on flawed premises.

In April 1965, hostilities flared in the Rann of Kutch, a sparsely populated, marshy region along the Gujarat-Sindh border. Pakistani forces initiated attacks near Sardar Post, Vigokot, and Biar Bet, aiming to test Indian resolve and claim territory. India responded with limited but firm military action, pushing back the intrusions. Though localised, the conflict exposed Pakistan’s intent and served as a prelude to broader aggression later that year. The Kutch skirmish set the stage for the 1965 war. ( Detailed account follows).

Operation Gibraltar

In August 1965, Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar, named after the famed Islamic conquest of Spain, suggesting high ambition and even higher symbolism. Thousands of armed infiltrators, many of them Pakistani soldiers in plain clothes, were inserted across the Line of Control into Jammu and Kashmir. Their mission: to incite a local uprising against Indian rule and spark a mass rebellion that would paralyse Indian forces and administration.

But the plan failed almost immediately.

The Kashmiri population, contrary to Pakistani expectations, did not rise in revolt. Far from it many villagers informed the Indian authorities about the presence of strangers in the area. The Indian Army reacted swiftly, sealing infiltration routes, neutralising saboteurs, and reasserting control over the Valley. What was meant to be a covert, subversive masterstroke ended up exposing Pakistan’s intentions and backfiring both tactically and strategically.

Faced with the failure of Gibraltar, Pakistan decided to escalate further with Operation Grand Slam, a conventional armoured offensive aimed at capturing the town of Akhnoor in Jammu and thereby cutting off India’s access to the Kashmir Valley. This marked the transition from a covert operation to open war.

A War of Choice

Thus, the 1965 war, from Pakistan’s side, was not a reaction to Indian aggression, it was a war of choice. It was premised on a chain of misjudgments, that India was weak, that Kashmir was ready to rise, that the international community would intervene quickly to freeze the conflict in Pakistan’s favour, and that China’s shadow would deter India from a full scale response.

What Pakistan discovered instead was that India was neither broken nor unwilling to fight. The Indian response, particularly the bold decision to open a front across the international border in Punjab caught Pakistan off guard and shattered the myth of a quick, contained conflict. The seeds of Pakistan’s failure in 1965 lay in its own strategic overconfidence, not in India’s supposed vulnerabilities. The stage was now set for a wider and more intense confrontation.

1965 Timeline : Key dates from April to August 1965

07 April 1965. The first shots rang out at Sardar Post. A Coy of CRPF was attacked in strength by a detachment of the Pakistan Army.

09 April 1965. The 51st Brigade of the Pakistan Army launched a full scale operation named ‘Desert Hawk’ – the Orbat comprised 18 PUNJAB; 8 FRONTIER FORCE & 6 BALUCH- simultaneous attacks were launched on Sardar Post and Tak Post. A Coy of 150 CRPF jawans held back a 3,500+ strong 51st Brigade. The exchange of fire lasted for more than 12 hours, and it cost the lives of 06 Indian and 34 Pakistani soldiers killed at Sardar Post. Subsequently, 150 Pakistani soldiers were wounded at Biar Bet. Skirmishes continued all through April.

26 & 27 April 1965. India lost Biar bet after an attack by Pak 15 PUNJAB at Chad bet. The Loss of Biar bet was a tale of heroism against heavy odds. The Pakistani attack was led by 24 CAV (FF) & 2 FF (Guides); The Indian 50 (I) Para Brigade paid a heavy price.

28 April 1965. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson wrote to Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and President Ayub Khan of Pakistan – suggesting a ceasefire; withdrawal of troops and subsequently a restoration of bilateral status quo and talks.

End April to 06 May 1965. While the Government of India accepted the offer for ceasefire at the suggestion of Harold Wilson, the British Prime Minister, it also ensured the deployment of all Indian Army units earmarked for deployment in Punjab to go in for a heightened state of Alert.

“Operation Ablaze” India’s Pre emptive Mobilisation before the 1965 War. It was launched in the XI and XV Corps AOR.

14 May 1965. Pakistan ordered an attack in the Kargil sector of Jammu and Kashmir to counteract the Kutch situation. The area was under command of 4 RAJPUT. The Coy Commander, Maj Baljit Singh Randhawa made the supreme sacrifice in the attack, but not before ensuring a strong push back- he was awarded Maha Vir Chakra, posthumously.

30 June – 01 July 1965. The ceasefire brokered by Harold Wilson came into effect from 0600h 01 July 1965.

July – August 1965. Pakistan lay low for a while soon after the failed moves in Kutch, but not for long. Large scale and sized infiltration commenced in Jammu and Kashmir throughout July ‘65. A flood of malicious propaganda was unleashed against the people in Jammu and Kashmir, and subversive activities planned by the Pakistan Army under Maj Gen Akhtar Hussain Malik, GOC 12 Inf Div began to take shape.

01-05 August 1965. The large-scale infiltration commenced in the garb of people entering the valley to celebrate the anniversary of Pir Dastgir Sahib, on 08 August 1965. The operation code named Gibraltar comprised a 30,000 strong force divided into 04 groups- converged from the areas: South West of Jammu, Poonch; Uri in the west; Tithwal in the northwest and Gurez in the north and Kargil in the northeast. The only way possible to stem this ongoing infiltration was to go on and offensive and cross the cease-fire line to plug their base camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. (detailed account follows)

13 – 14 August 1965. The 17 PUNJAB was deployed in the Kargil sector, mounted a stealth attack on Point 13620 Complex, led by Maj Balwant Singh, OC ‘D’ Coy- they captured Point 13260, Saddle and Black Rock.

23 August 1965. Capture of Tithwal- 1 SIKH less two companies; 138 Mountain Battery & 17 Mountain Battery of 7 Field Regiment mounted an attack on Richhmar Gali (RMG) & captured the ridge by 2300h.

25 August 1965. Capture of Pir Sahiba. Here also, the 1 SIKH and 138 Mountain Battery attacked a formidable picket of Pir Sahiba under the cover of darkness. Capture of Pir Sahiba ensured the Indian Army to watch the routes of infiltration.

25 – 28 August 1965. Capture of Haji Pir Pass. Situated at a height of 8,652 feet, the Hajipir bulge was vital link between Uri and Punch. It is dominated by three peaks – Bedori in the east (12,360 ft); Sank in the west (9,498 ft) & Ledwali Gali in the southwest (10,302 feet). (detailed account follows)